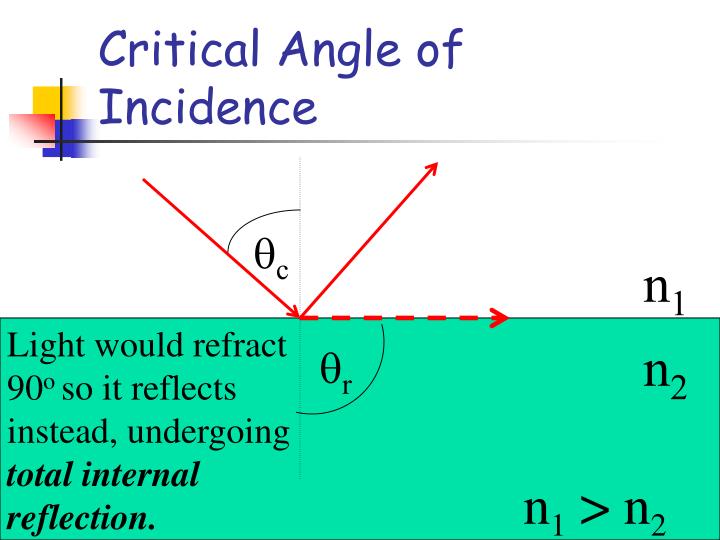

Shooting directly into an on-axis background is easily accomplished by using an off-camera light source positioned to the left or right of the camera. Some situations with an on-axis background include photographing flat art, showing a person in front of a large window, or showcasing a feature of an architectural interior. However, there may be times when you may want the wall on axis behind your subject. (figure 4)įigure 5 shows the improved result when we change an on-axis flash to an off-axis flash. In the diagram of figure 4 we see that the camera is now off-axis from the wall, and the reflection from the camera flash is no longer bouncing back into the lens. Taking a few steps to one side or another causes the (camera mounted) flash to hit the background surface at an oblique angle, so the light misses the camera when it bounces back. The hotspot of light from a surface behind our subject perfectly illustrates that a flash aimed directly at a wall or window (on-axis) will bounce directly back at us. ‘On-axis’ flash, creating the ‘bounce back flash’ that frequently ruins photos, is shown in fig. If the on-camera flash is fired when the camera is on-axis, a direct incident reflection results, as illustrated. When the camera sensor is parallel to a surface in the photo, we call it ‘on-axis’ positioning. This occurs when the light from a flash hits a surface that’s parallel to the camera sensor and bounces right back at the camera. One of the most common problems in flash photos is the ‘flashback’ reflection behind the subject. That’s the most basic illustration of the concept, but as we’ll see, there’s a lot more to consider. Finally, we’ll explore the useful and fun aspects of the angle of incidence.In this simple diagram we see that a beam of light enters from the left, strikes a surface, and exits to the right at the same angle. Then we’ll provide solutions to problems that arise from unintended reflections. This often mentioned law of lighting physics is easily demonstrated, as in the photo of me holding a laser pointer, but how can it be used for creative purposes? In this lesson we’ll show you how the angle of incidence works in scientific terms. Understanding additive and subtractive lighting.Using reflections to achieve interesting effects.Avoiding common problems from unwanted reflections.Learning about this aspect of lighting all begins with the phrase: The angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. We don’t think about the physics of light and reflections very often, but a basic understanding of light theory can be helpful. The surfaces might be skin, water, leaves, flowers, clouds, buildings, even the sky, but they’re all reflections. Unless your camera is pointed directly at a light source, like the sun or a light bulb, you’re photographing light reflecting off of a surface. And a direct consequence is that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection.Almost all photographs are simply a record of reflections. This is known as "Fermat's law of refraction," and it says that light seems to magically find the shortest-time path between two points. But if the path is either the fastest or slowest path from point A to point B, then something magical happens: all of the nearby paths take about the same time, so all of the arrows line up, so you get a very large probability that the object moves in that way. If they all have a different time then each arrow is tilted a little more relative to the last one, and as you add them together, they describe something very circle-like and it will not get far away from the initial point. Now if there is a path, and there are other possible paths "nearby" that one, like on a mirror, we have to consider if they take a different time or not.

We add up all of these little arrows by connecting them tip-to-tail and then ask how far away the final point is from the initial point, which is a measure of the probability that the photon goes in that direction. Each path can be thought of as a little arrow rotating in 2D at a constant rate with respect to time (the photon's "frequency"). Our modern understanding is that a photon is able to sense every path that it could possibly take from A to B. So a single atomic electron that gets excited in this way indeed does not have this property, and indeed a vast number of them can do this in parallel without functioning this way: this is part of the classical explanation for why the sky is blue.įurthermore it matters that the surface is flat: if you cut little parallel lines in the surface then you get a spectrometer this is part of the explanation for why you see rainbows in the "data track" of a CD or DVD.įurthermore you see the same reflection when you analyze things like reflection from a glass, even though there is also a transmitted wave.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)